Budō – The martial ways of Japan

BUDŌ

Budō, the martial ways of Japan, have their origins in the traditions of bushidō – the way of the warrior. Budō is a time-honoured form of physical culture comprising of jūdō, kendō, kyūdō, sumō, karatedō, aikidō, shōrinji kempō, naginata and jūkendō. Practitioners study the skills while striving to unify mind, technique and body; develop his or her character; enhance their sense of morality; and to cultivate a respectful and courteous demeanour.

The term “bushidō” was created by bushi (or samurai), to reflect on their “way of life” as professional warriors, and encompasses their values and moral outlook.

The morals of bushidō to live honorably and virtuously were a product of an appreciation for the beauty of life discovered through experiences of mortal combat. The spirit of autonomy, fundamental to bushidō, is an inherent feature in the modern martial arts. Through the study of budō, the individual is able to develop his or her sense of dignity and simultaneously learn respect for others. Although the question of life and death is not a concern for modern martial artists as it was for bushi, respect, honour, and love for life remain as a vestige of the spirit of bushidō.

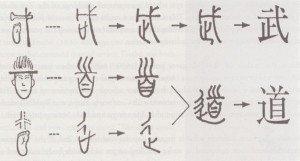

Budō is composed of two kanji characters. Bu first meant to go into battle, but this later came to be interpreted as “to stop fighting”. Dō symbolizes the movement of a man, or “the Way”.

Modern budo arts such as jūdō, kendō, karatedō, aikidō, naginata and so on, have their roots in the classical martial schools developed from the Heian period (794 – 1185) through the Tokugawa period (1600 – 1868). The various forms of budō that were systemized and established from the Meji period (1868 – 1912) and beyond are broadly categorized as gendai budō (modern budō). All martial arts created before this time are referred to as kobudō (classical budō).

Broadly speaking, kobudo arts can be categorized into the following groups:

– Bajutsu (horsemanship)

– Kyūjutsu (archery)

– Kenjutsu (swordsmanship)

– Sōjutsu (spearmanship)

– Naginata-jutsu (glaive)

– Bōjutsu (staff)

– Kama-jutsu (sickle)

– Jūjutsu (close-quarter combat with small or no weapons)

– Sui-jutsu (tactical swimming)

– Hōjutsu (musketry)

In budō, training is generally referred to as “keiko”. The kanji for keiko literally means “to consider [the wisdom] of the past”. One of the important methods used to convey this wisdom is the study of kata – choreographed sequences of techniques.

Kata are an integral part of the curriculum of budō, and contain the technical and philosophical essence of the founders’ teachings. Novices begin their study of budō by duplicating the kata exactly as it is taught by the master, avoiding any deviation from the prescribed form.

Important element of keiko and learning kata is self-reflection and problem solving. In Japan’s traditional arts, there is a concept called “ishin-denshin” or “thought transference”. Masters use few words to explain the intricacies of the techniques being taught. Much is left up to the disciple to figure things out for themselves, which requires considerable introspection and analysis. Even though the process begins with precise copying, it eventually facilitates the growth of true individual attributes and a penetrating sense of imagination. The instructor oversees this development in the student, and teaches in a way that encourages the burgeoning of individuality. Temperament, independence and individuality are the factors that lead to the development of art.

Budō is a gateway of immense breadth and depth to spiritual development. You can almost touch hands with the warriors of centuries ago as you immerse yourself in the training of kata. However, if your mind is closed to the possibilities, the gate will remain closed.

Instructors of budō should bear in mind the following points to improve the overall efficacy of budō education:

1. Be aware of the characteristics of each child, and make allowances to accommodate their individuality.

2. Keep attuned to what children are doing outside the dōjō and club activities. Be sure to impress upon that etiquette taught in the dōjō is not limited to the dōjō or their immediate social circle.

3. Be aware that children are always observing and learning from you; so be careful to demonstrate humility in word and action.

4. Make the budō training area open for parents to visit. You should listen to parents’ comments, acknowledge them, and show them you have the children’s best interests at heart.

5. Have a firm budō education policy and regularly convey it to children and parents.

6. Do not say anything that may hurt a child who has stopped coming to training. Instead, praise all of his or her achievements to date, and help them acquire a positive self-image rather than ostracise the child for being a “quitter”.

KARATEDŌ

The “Way” of karate (karatedō) is one of Japan’s most famous martial arts. It is an art of self-defense that, for the most part, uses no weapons, hence the meaning of karate – “empty hand”. There are three main categories of techniques: strikes with the arm (uchi); thrusts (tsuki); and kicks (keri). There are also a number of blocks (uke) to parry the opponent’s attacks.

There are many theories surrounding the roots of the term “karate”. It is unclear who first used the word, and when. However, the ancient Ryūkyūan fighting system was originally referred to as “te”, and the standard assumption is that the appellation “kara-te” refers to the martial techniques learned from China (kara = China).

Karateka are taught the importance of never hurting other people, and to be respectful of opponents and training partners. This respect ideally extends beyond the confines of the dōjō and match court. Practitioners also learn perseverance, and the importance of making efforts to improve their immediate surrounds. A concern and appreciation for others and sense of responsibility to society, are fundamental to karatedō’s ultimate goal of self-perfection.

Funakoshi Gichin (1868 – 1957) created a set of twenty dōjō rules (dōjō-kun) from which five articles were extracted and promoted as the fundamental concept of karate:

1. Never forget that karate begins and ends with a bow of respect;

2. There is no first attack in karate;

3. Know yourself first, then you can know others;

4. The art of developing the mind is more important than the art of applying technique;

5. In combat, you must discern vulnerable from invulnerable points.

BUDŌ TERMINOLOGY

Dōjō

The word dōjō is a translation of the Sanskrit term “bodhimanda” and refers to the “Diamond seat” – the seat upon which the Buddha attained nirvana, enlightenment, under the Bodhi tree. Accordingly, it is used in reference to a place where Buddhism is studied or where sermons are delivered. It is because of the deep spiritual connotations and relationship to training one’s self that the word was adopted into budō parlance.

Seiza

Seiza is the formal kneeling position where the budō practitioner is calm and resolute. Sitting correctly in this position is synonymous with following the “way” of budō. It is also a waiting posture that represents the ideal of fair play towards one’s opponent.

Dan and Kyu Grades

Dan grades have played an integral role in the traditional cultural pursuits in Japan, and were first employed by the shōgi (traditional form of chess) master, Hon’inbō Taisaku (1645 – 1702), as early as 1677.

The dan system was first introduces into the martial arts in 1883 when Tomita Tsunejirō and Saigō Shirō were awarded the rank of shodan in Kodōkan jūdō. The kyu system was first introduces in 1885 by Keishichō (Tokyo Police Bureau).

Reference

Budo: The Martial Ways of Japan. Nippon Budokan Foundation, Tokyo, 2009.

Summary by Christophe Delmotte – International Kyokushin Organization Tezuka Group – 2014